Published: December 14, 2025

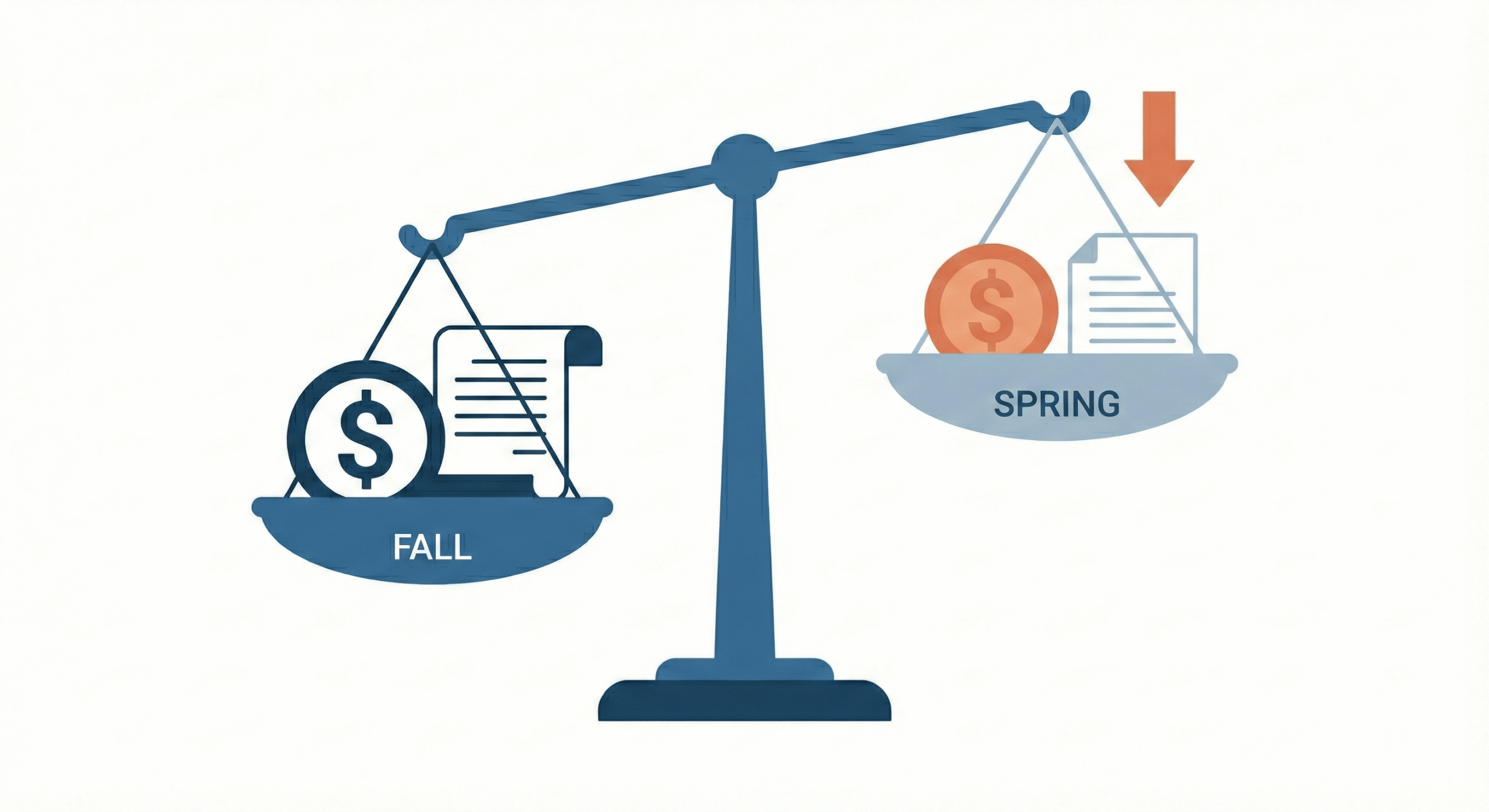

Fall semester sets expectations. The aid arrives, the balance looks manageable, and the system feels predictable. Spring breaks that illusion. The bill is higher, the aid line is smaller, and the explanation sounds vague. What looks like a mistake is usually the result of federal rules quietly recalculating eligibility months earlier.

According to Federal Student Aid, annual award amounts are typically divided equally between fall and spring terms. However, numerous regulatory factors, including course enrollment timing, satisfactory academic progress reviews, and fund depletion, can reduce spring semester disbursements.

The assumption that aid remains constant throughout the academic year creates significant financial planning gaps. Students whose budgets are based on fall disbursements may discover that spring funding does not materialize at the same level.

Data reflects federal guidance available through early 2026.

Annual Awards Split Across Terms

Most financial aid programs calculate eligibility annually but disburse funds per term.

A hypothetical $6,000 Pell Grant does not arrive as a single payment. It is structurally divided into $3,000 for fall and $3,000 for spring, contingent on full-time enrollment for both semesters.

Federal Direct Loans follow similar patterns. If a student is approved for $5,500 in subsidized loans annually, they receive $2,750 per semester. The annual award letter received in the spring shows total eligibility, not per-semester amounts.

Institutional grants and state aid programs use the same split methodology. A $4,000 annual merit scholarship becomes $2,000 per term. Students who see an annual total often expect that amount each semester, rather than the split figure.

Confusion tends to emerge when fall semester aid covers the bill comfortably. Rising spring tuition costs, changing fees, or altered housing arrangements can make the second-half disbursement feel inadequate even when it technically matches fall amounts.

Enrollment Status Changes

Financial aid eligibility is tied directly to credit hours enrolled. Full-time status typically requires 12 credits per semester, and many aid programs reduce or eliminate funding for students below this threshold.

Students who took 15 credits in the fall but drop to 9 in the spring may see dramatic aid reductions. U.S. Department of Education regulations require Pell Grants to prorate based on enrollment intensity. Under these rules, grant funding is recalculated as a percentage of full-time enrollment.

Late course registration creates another complication. If a student registers for fall classes before the enrollment census date but delays spring registration until after aid disbursement calculations, the system may process spring aid based on zero enrolled credits.

Dropping courses after the add/drop period can trigger aid recalculations. Students who reduce credit hours mid-semester may face “Return of Title IV Funds” requirements, where the college must send back aid to the federal government.

Satisfactory Academic Progress (SAP) Failures

U.S. Department of Education regulations require students to maintain Satisfactory Academic Progress (SAP) to remain eligible for federal financial aid.

Fall semester grades do not post until after winter break, and SAP reviews often occur in early January before spring disbursements. Students who failed courses or withdrew frequently may lose eligibility for the spring term based on fall performance.

Federal completion rate requirements generally mandate students successfully complete at least 67% of attempted credits. Taking 15 credits but passing only 9 could violate this standard even if the GPA remains acceptable.

Maximum time frame limits also affect students. Federal regulations limit aid eligibility to 150% of the published program length. Exceeding this cap results in a loss of federal aid regardless of current academic performance.

Fund Depletion And Budget Exhaustion

State grant programs often operate on first-come, first-served annual budgets. States may fund fall semester awards but deplete their allocation before spring disbursements, particularly in years with higher-than-expected enrollment.

Institutional aid from college endowments follows similar constraints. Schools allocate scholarship budgets annually, and unexpected costs can force mid-year reductions when funds deplete faster than anticipated.

Federal Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grants (FSEOG) are campus-based programs with limited funding. Colleges receive fixed allocations; once fall funds are exhausted, spring funds may not be available.

Federal Work-Study positions face earnings limits. If a student reaches their annual work-study award maximum during the fall semester, no additional work-study funding remains available for spring employment.

Verification And Documentation Delays

The FAFSA verification process can delay or reduce aid disbursements. If an application is selected for verification after fall aid already disbursed, spring funding might be held until required documentation is submitted.

Discrepancies discovered during verification can reduce aid retroactively. If verification reveals reported income was lower than actual earnings, spring aid may decrease to correct for fall overpayment.

Dependency override approvals sometimes expire. Students who received fall aid through a dependency override may need to reapply for spring, and delays in approval can prevent timely spring disbursement.

Tax filing delays create problems for continuing students. If taxes for the required year are not filed, spring aid may be withheld even if fall aid processed without issue using prior year information.

Half-Time Enrollment Complications

Some aid programs require full-time enrollment for initial eligibility but reduce awards for part-time status. Students who shifted from full-time in fall to half-time in spring see prorated reductions.

Pell Grants adjust based on enrollment intensity. Depending on the Student Aid Index (SAI), a student in recent award years receiving $3,698 for full-time fall could see that amount reduced to about $1,849 when dropping to half-time in spring.

Subsidized loan eligibility follows similar rules. The annual maximum of $3,500 for dependent first-year students does not divide evenly if one semester is full-time and the other is half-time. The spring disbursement recalculates based on current enrollment.

Institutional scholarships may have different standards. Some require full-time enrollment every semester, meaning any drop below 12 credits eliminates the entire award.

Loan Limit Exhaustion

Federal Student Aid enforces strict annual borrowing limits. Dependent first-year students are currently capped at $5,500 in Federal Direct Loans annually.

If a student borrowed the full amount in the fall plus additional unsubsidized loans, borrowing capacity may be exhausted before spring. Annual loan limits do not reset mid-year.

Students who maxed out federal borrowing in the fall cannot access additional federal loans for spring even if financial need increased.

Private student loans may have similar constraints. Lenders who approved fall semester loans sometimes reassess eligibility before spring disbursement. Changes in credit scores or income can reduce approved amounts.

Common Administrative Protocols

Award Letter Audits: A line-by-line review of the financial aid document clarifies whether amounts listed are annual totals or specific per-term disbursements.

Enrollment Validation: Matching registered spring credits to the enrollment intensity used for aid calculations prevents unexpected proration adjustments.

SAP Status Monitoring: Accessing the student portal immediately after fall grades post reveals whether completion rates or GPA metrics triggered a suspension warning.

Documentation Submission: Immediate resolution of verification requests or paperwork delays prevents administrative holds from blocking the spring disbursement.

Contingency Budgeting: Financial plans often account for potential shortfalls, ensuring emergency funds or alternative financing options are identified before the billing cycle closes.

Spring semester aid reductions are rarely random or punitive. They reflect timing rules, enrollment thresholds, and budget limits that operate independently of fall outcomes. Understanding these structural mechanics helps explain why spring balances often rise even when circumstances appear unchanged.

This article provides general information about financial aid disbursement patterns and regulatory factors affecting semester-to-semester aid amounts. Individual circumstances vary significantly based on institution, aid programs, and student status. School Aid Specialists states that final authority on specific disbursements rests with the institution’s financial aid office.

Sarah Johnson is an education policy researcher and student-aid specialist who writes clear, practical guides on financial assistance programs, grants, and career opportunities. She focuses on simplifying complex information for parents, students, and families.